Duterte in the ICC: An End, Finally, to Impunity in the Philippines?

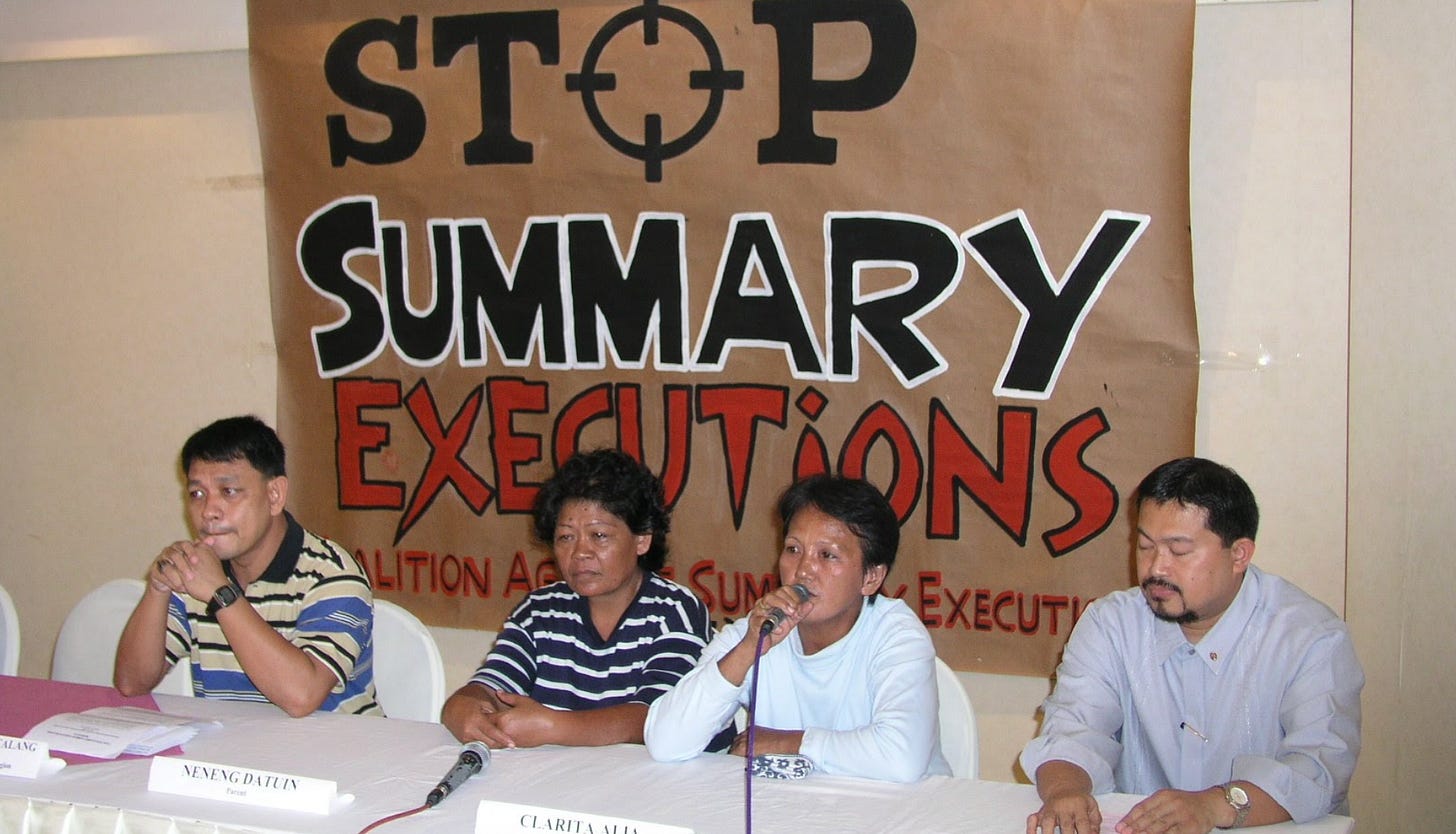

Clarita Alia speaks at a press conference in 2002, a year after the first of her four sons were killed by the Davao Death Squad. She and other families of victims in Davao City accused then mayor and later president Rodrigo Duterte of ordering the murders.

By Carlos Conde

The International Criminal Court’s confirmation of charges against former President Rodrigo Duterte is happening on Feb. 23 in The Hague. The court announced this alongside its determination that Duterte, who has been in ICC detention for almost a year now, is healthy enough to stand trial. But this isn’t just another legal box being ticked or a technicality being hurdled. For the families who lost people they loved in Duterte’s so-called “war on drugs,” this is something deeper — a recognition that their grief and their losses actually matter.

Groups like Human Rights Watch (where I used to work) have documented case after case of unlawful killings that happened and hardly anyone being held responsible. Take Kian delos Santos, a 17-year-old student who was dragged into an alley by police in Caloocan City and shot dead in 2017. The police claimed he fought back. CCTV footage and witnesses told a different story. His last words — “Tama na, may exam pa ako bukas” (Enough, I have an exam tomorrow) — cut through all the official lies and became a rallying cry across the country.

Or Carl Angelo Arnaiz, 19, arrested by police in Cainta in 2017 and later found dead with gunshot wounds. The authorities said he tried to rob a taxi driver and resisted arrest. Forensic evidence said otherwise. His friend, Reynaldo de Guzman, disappeared after police took him and was eventually found dead, his body wrapped in plastic. Human Rights Watch and others showed how these police stories fell apart under scrutiny, revealing a clear pattern of lies and abuse. (Although Kian’s and Carl’s murderers have been found guilty by the courts, their higher-ups remain untouched by the Philippines’ notoriously slow, compromised, and inefficient justice system.)

Then there’s Jennifer, who was 12 when she watched police gun down her father during a raid on their home in Payatas, Quezon City. When I interviewed her for this HRW report, the trauma was right there on the surface—nightmares, anxiety, a deep mistrust of anyone in uniform. Years later, from what I’ve heard from rights defenders who continue to monitor her case, she’s still haunted by it.

And Clarita Alia, who lost four sons in separate incidents in Davao City between 2001 and 2007. Technically, those deaths fall outside the ICC’s timeframe, but they’re a chilling reminder of the violence Duterte unleashed first in Davao City where he was mayor and then, starting in 2016 when he became president, across the entire country. Four sons. One mother. No justice. Her story shows the moral nightmare of a policy that treated death as normal and murder as part of governance.

These aren’t isolated incidents or faceless numbers. These are real lives ripped apart — families raising kids without fathers, siblings without brothers, entire communities living with fear and loss. And overwhelmingly, it’s poor people who bore the brunt of this violence.

For these families, the ICC case isn’t about geopolitics or legal theory. It’s about accountability. It’s about being able to tell their children that their fathers weren’t criminals who “deserved” what happened to them. It’s about giving back some dignity to both the dead and the living.

This moment should also be a wake-up call — and an opportunity — for the Marcos administration and for Filipinos. We can’t move forward if people in power never face consequences for their actions. Our own authorities here could and should take action against impunity. But aside from some talk and empty promises, the Marcos administration has done virtually nothing. The “drug war” policy is still very much alive, for example.

Still, if accountability is allowed to happen — even through an international court — it sends a message that maybe, just maybe, the era of getting away with murder in the Philippines might be coming to an end.