The Priest, Duterte's Death Squad, and the ICC

Weeks before he died in May 2024, Father Amado Picardal wished that the feud between the Marcoses and the Dutertes would lead to the political demise of the Dutertes.

By Aie Balagtas See

Rights Report Philippines

Days before Fr. Amado Picardal died of a heart attack on May 29, 2024, the 69-year-old human rights champion had a rosy outlook for justice in the Philippines. He hoped the quarrel between the families of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. and his vice president, Sara Duterte, could finally end the reign of the Dutertes in Philippine politics.

“He was very optimistic that this tension between the two camps was worsening and, you’ll never know, that this would be the end of the Duterte dynasty,” said Karl Gaspar, the religious brother whose friendship with Picardal spanned 37 years. “He was sort of very pleased with that.”

Gaspar spoke with Rights Report Philippines at Picardal’s wake in Cebu City, days after he died of a heart attack while tending to his garden in that city. Before Picardal’s passing, the feud between the Dutertes and the Marcoses had already erupted. Both families had coalesced for the 2022 elections that propelled Marcos Jr., the son of the late dictator, to the presidency.

Less than a week ago, Sara Duterte announced that she’s running for president in 2028 and expressed regret for supporting Marcos Jr. in the 2022 elections. Many had assumed that Duterte would run for president in that election but chose instead to form what later became the “uniteam” with Marcos Jr.

Gaudeamus

Both Gaspar and Picardal were members of the Redemptorist Church in Cebu. The two met weekly at their Monday get-together called gaudeamus, where they talked and caught up with each other over a meal before dinner. Picardal, though living as a hermit since 2022, regularly joined the gathering as part of the Redemptorist community dynamics.

On the last two Mondays of his life, Picardal’s health was deteriorating. He had diabetes and hypertension but refused to see a doctor. But at the dining hall with his confreres, Picardal was effervescent. And he never failed to put politics on the table.

According to Gaspar, he “constantly” updated everyone about news on the ICC, where the former president is facing crimes against humanity charges. Fr. Picx, as friends and colleagues fondly called Picardal, insinuated that the developments might lead to an arrest warrant for Duterte.

“We have been very concerned because he is the number one concerned about what was going on. Apparently, people from ICC continued to be in touch with him. And so, he was very glad that the squabble could make Marcos allow the investigators from ICC to enter, and from there, this could lead to the downfall of Duterte,” Gaspar said.

Gaspar recalled one of them asking: “Will they arrest him? ICC has no police power.”

Picardal replied: “Yeah, but at least he cannot travel anymore. Because when he is in another country, they will arrest him. Maybe, not in the Philippines.”

As things turned out, acting on a warrant of arrest issued by the ICC, the Interpol arrested Duterte in March 2025 and was brought to The Hague, where he is now detained as a suspect. The Pre-Trial Chamber 1 of the court will conduct confirmation of charges hearings against Duterte beginning on Monday, Feb. 23, to determine if the evidence against him is sufficient to bring the case to trial.

Hermitage

Picardal died past noon on May 29, 2024, in Lahug, Cebu City, near the hut he built for the hermitage. The son of a health worker found him lying face up around 2 p.m. He was already dead. There was no foul play.

It was unclear why he refused to see a doctor but Brother Ciriaco Santiago III, a Redemptorist colleague, presumed that it was because Picardal detested hospital confinement so much.

Being alone in a hospital room depressed Picardal. It reminded him of the torture and seven-month imprisonment he endured under Marcos’s Martial Law. Picardal also worried that Duterte’s henchmen might find it easier to kill him if found alone in a hospital bed.

Santiago said when caretakers found Picardal’s body, they noticed that his hands were in a position that seemingly wanted to move. “It seemed like he still wanted to get up but couldn’t anymore,” Santiago told Rights Report Philippines.

Mayor’s Wrath

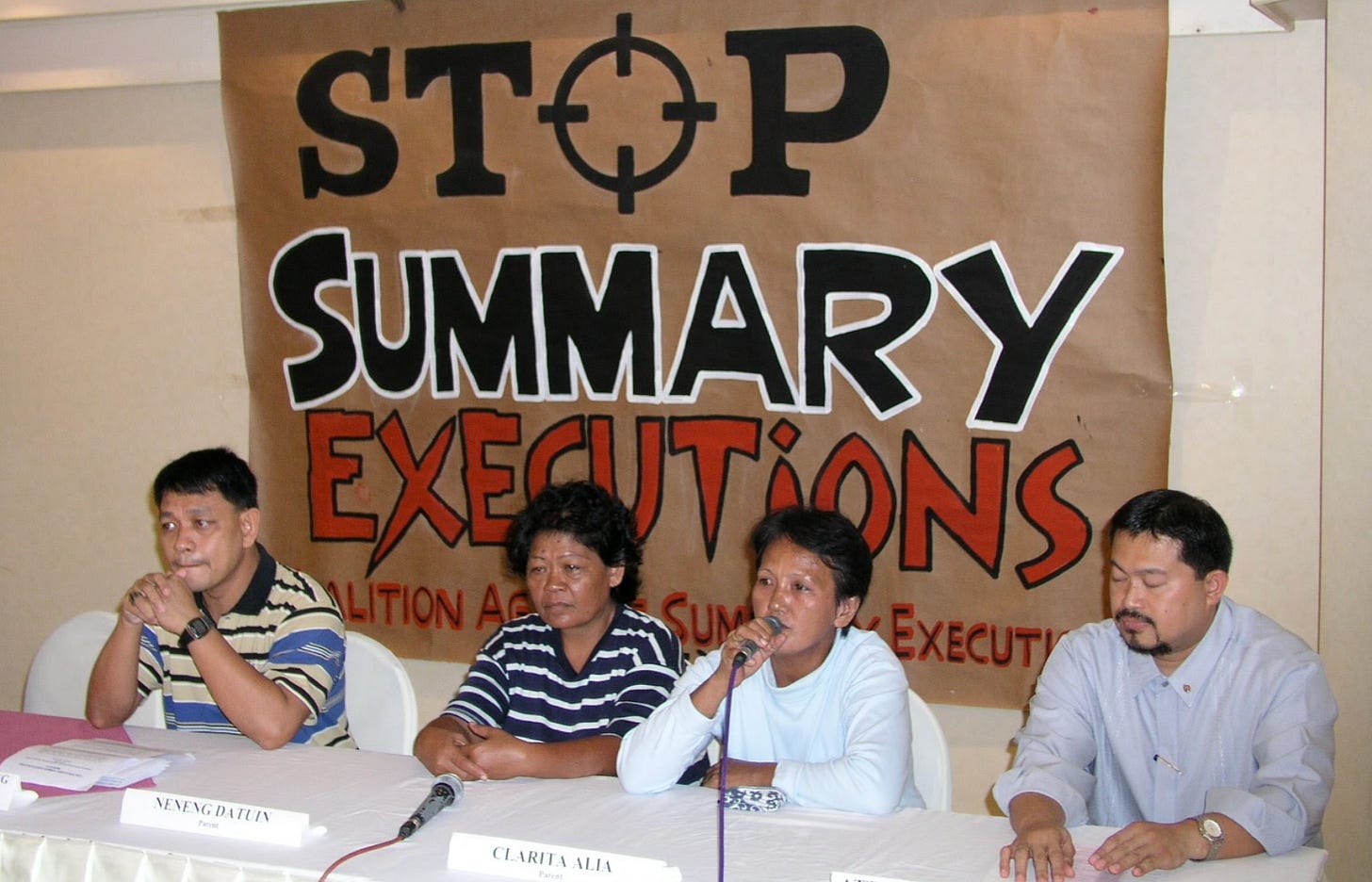

Picardal was one of the first to sound the alarm on the killings perpetrated by the so-called Davao Death Squad when Duterte was still mayor. He cofounded the Coalition Against Summary Execution (CASE), which helped expose and document the killings from the late 1990s to the early 2000s.

His determination to stop the summary executions earned Duterte’s ire and raised eyebrows among his supporters. In a 2006 blog post titled Mayor’s Wrath, Prophetic Vocation, Picardal recounted a warning he received from a friend: “The mayor is so mad at you, you’d better watch out he might order his death squads to go after you.”

“I want to live up to a hundred. I want to grow old and celebrate the golden jubilee of my ordination to the priesthood. But I choose not to be silent, I choose to speak up and denounce evil in our midst. If it means been (sic) picked up, imprisoned, or gunned down, so be it. I am not afraid to suffer, I am not afraid to die,” Picardal wrote.

He persistently denounced extrajudicial killings in his sermons and writings. He was dogged in the documentation, which, 10 years later, would assist the ICC in its case build-up against Duterte.

“He was a main witness in the ICC but never elaborated his participation there,” said retired Bishop Emmanuel Cabajar, a friend of Picardal’s.

Fearless

Picardal was assigned in Davao from 1995 to 2011. His life became entangled with victims of summary killings in 1998 after the youth group Tambayan repeatedly approached him each time they needed someone to hold a funeral mass for members who unidentified gunmen shot.

Tambayan Center for Children’s Rights Inc. is a nongovernment organization based in Davao City. Several of its members were killed by the so-called Davao Death Squad.

Picardal was fearless in his resolve to protect life and serve the poor. At times, he was also the only priest in Davao who went to these funerals and did it without any qualm.

The deaths in Davao eventually piled up to a number that was difficult for anyone to ignore. As the numbers grew, so did Picardal’s voice in denouncing it.

He wrote a detailed report which a lawyer, Jude Sabio, used in filing the first case against Duterte at the ICC, in 2017.

Picardal’s participation was supposed to be limited to the documents. Still, in the winter of 2020, while the Covid-19 pandemic halted the world, Picardal stood up and left his office in Rome to go to The Hague.

He never elaborated on his testimony even to bosom buddies. Those who knew refrained from inquiring to protect Picardal and the sanctity of the investigation. “It was like there was an unwritten agreement among those in the know that we should never talk about it,” an insider told this reporter.

Duterte’s rise to power failed to cow Picardal who managed to bring his fight to a national level.

“Now is not the time to be afraid,” Picardal told me in November 2016, adding “There will be cases to be filed in the near future.”

Cunning

Throughout his battle, Picardal openly condemned not only the killings but the “silence of the shepherds” as well. In 2018, he reminded members of the clergy that silence is consent.

In a blog post, Picardal said he hoped priests would find their voice and courage “to form the moral conscience of their flock so that they may recognize and denounce the manifestation of evil and the culture of death.”

Cabajar described Picardal as a cunning and calculated man who refused to make decisions based on speculations. This was why, the bishop believed, Picardal kept himself safe all these years.

Cabajar said Picardal cultivated sources among the intelligence community who warned him of dangers that were about to come.

In 2018, the warnings became difficult to ignore, forcing him to cut his hermitage short. Men in motorcycles had been looking out for him, forcing Picardal to move to Lipa City while waiting for his new assignment in Rome. The ICC would reach out to Picardal from Rome.

Unfinished Business

He initially declined invitations to testify before the court. As part of the ICC rules, witnesses must be present in its headquarters at the Hague when giving their testimony.

“I’m done,” he told two people close to him. After all, he had already given Sabio, the lawyer, pertinent documents needed to look into the Davao killings. But when told about the gravity of his testimony, Picardal agreed to testify.

Picardal quietly went home to Cebu in 2022 to continue his hermitage that was cut short by threats to his life.

As his hut made of amakan neared completion, Picardal spent more time under the sun. Caretakers had warned Picardal that he should seek help or at least take a break when the heat was intense. But he refused both. The construction of its roof was nearing completion when he passed away.

“He was announcing that the hermitage will be finished sometime in June. Already telling us once it’s finished we will know immediately so we can all go up and celebrate and have a blessing,” Gaspar said.

Picardal had wanted to build the hut independently, cook his food, and tend to his garden. He believed life as a hermit was his next calling.

He wanted to live up to 100. He wanted to celebrate his 50 years with the Redemptorists. He would have wanted to witness the arrest warrant issued against Duterte.

Fr. Edilberto Cepe, the provincial superior of the Redemptorists in the province of Cebu, said a big part of the community went away with Picardal’s death.

”When he died, a part of the generations of the Redemptorists was also gone. The big man at the forefront of human rights is already gone,” Cepe said.

Cepe said Picardal eagerly anticipated the day the court would issue the arrest warrant. “He was looking forward, and happy, that something would finally come out of his efforts,” Cepe said. (Rights Report Philippines)

This story is free for republication or reposting as long as proper attribution or credit is given to Rights Report Philippines.